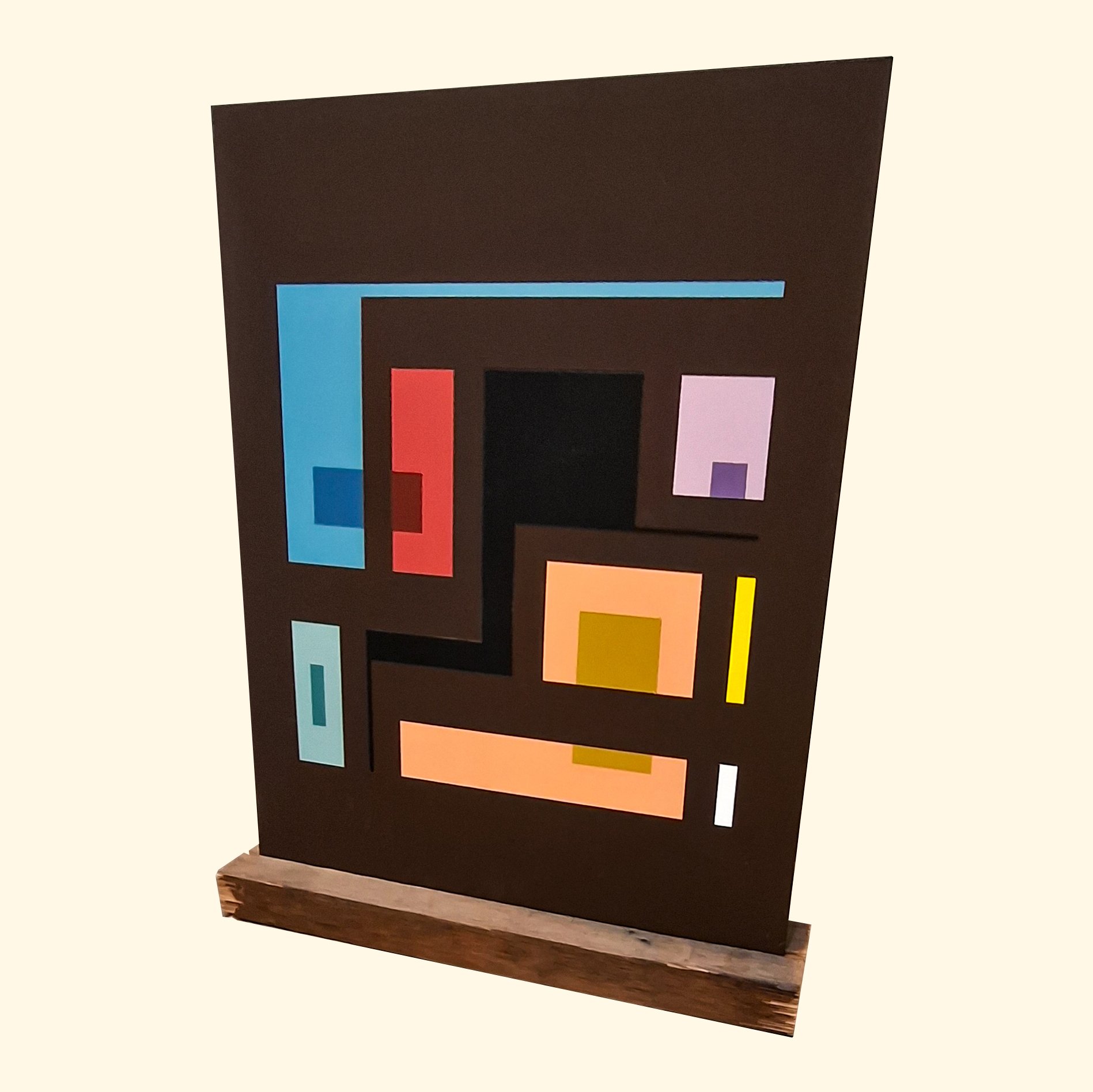

Image 1 of 4

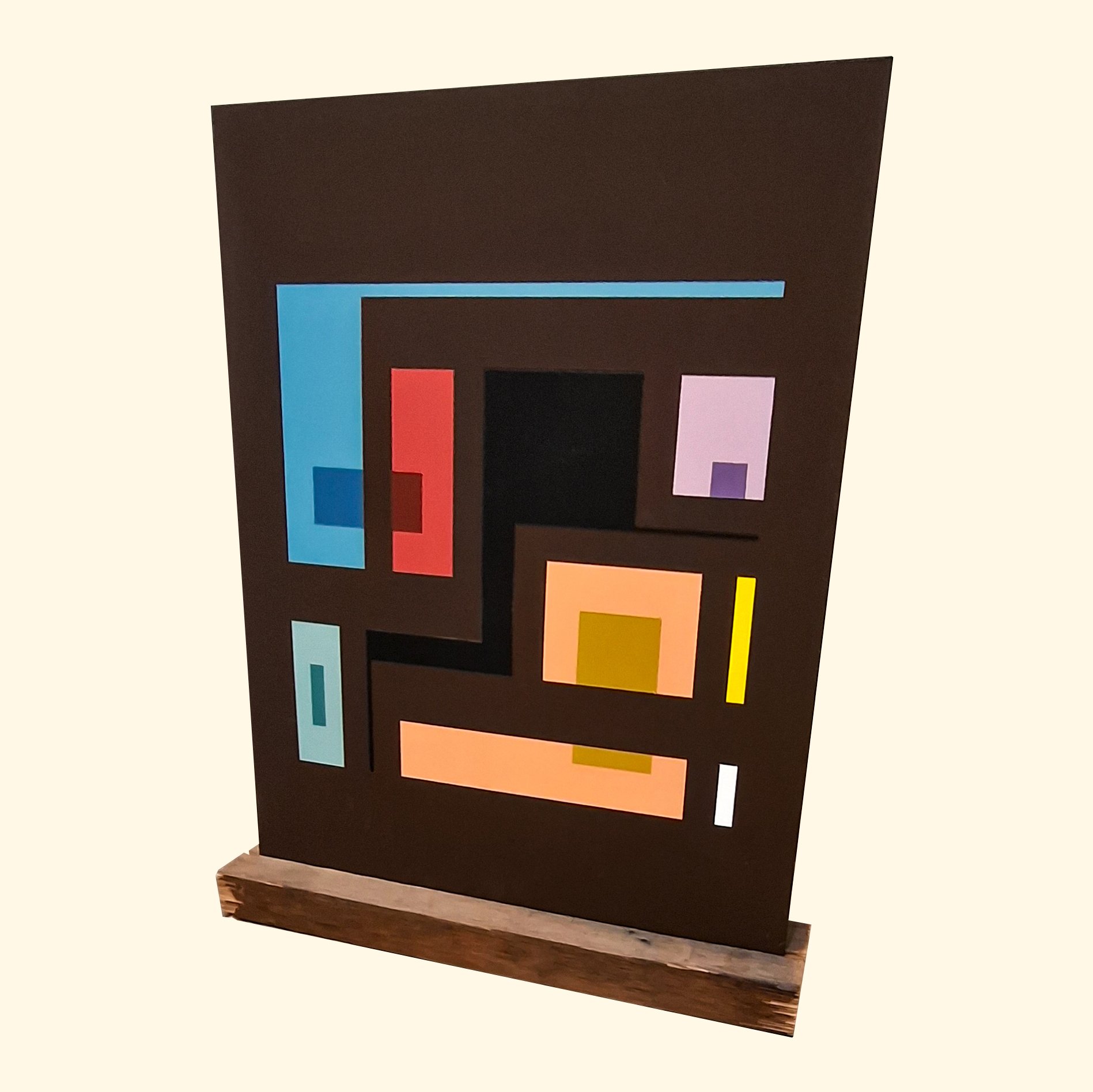

Image 1 of 4

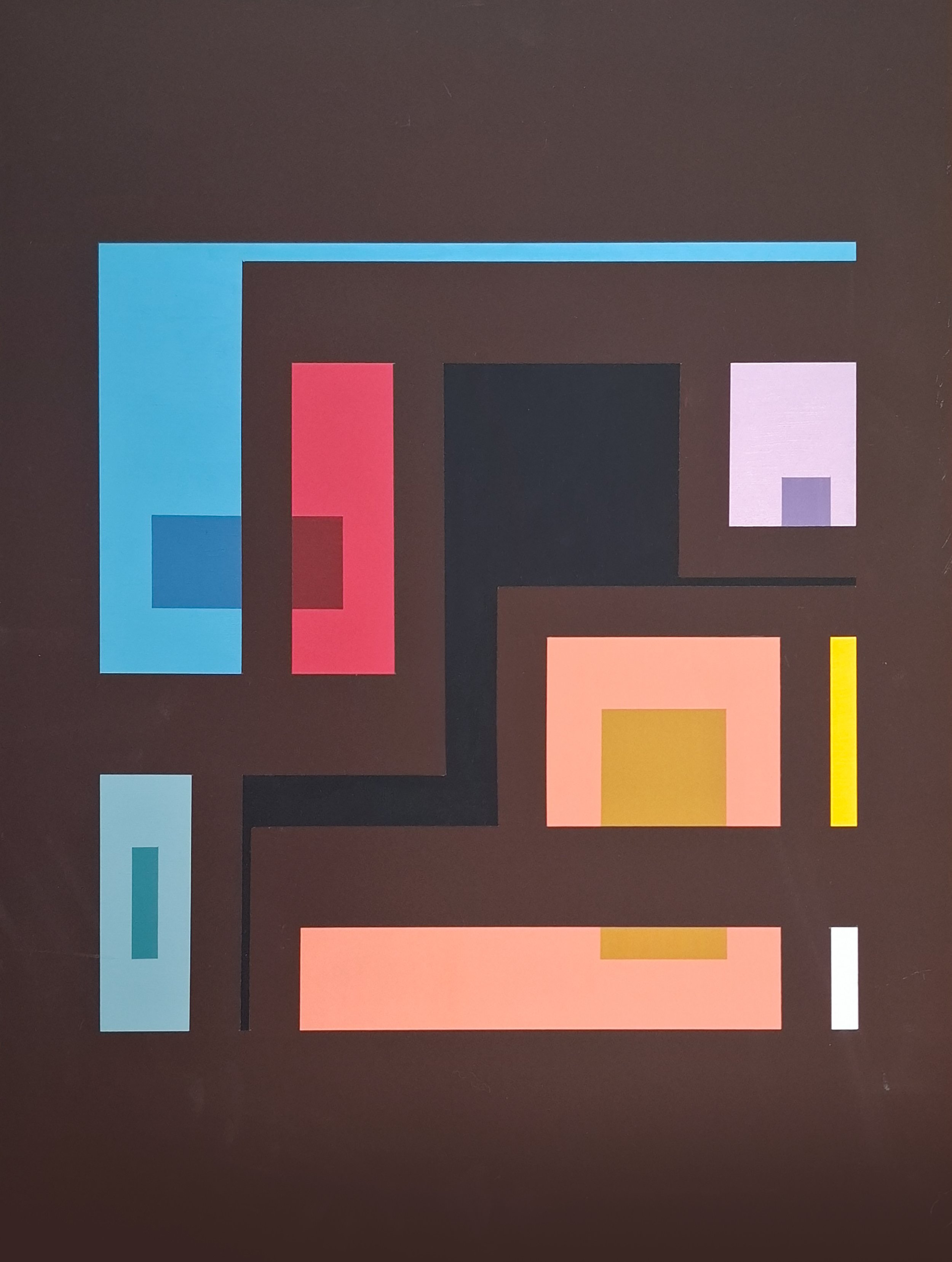

Image 2 of 4

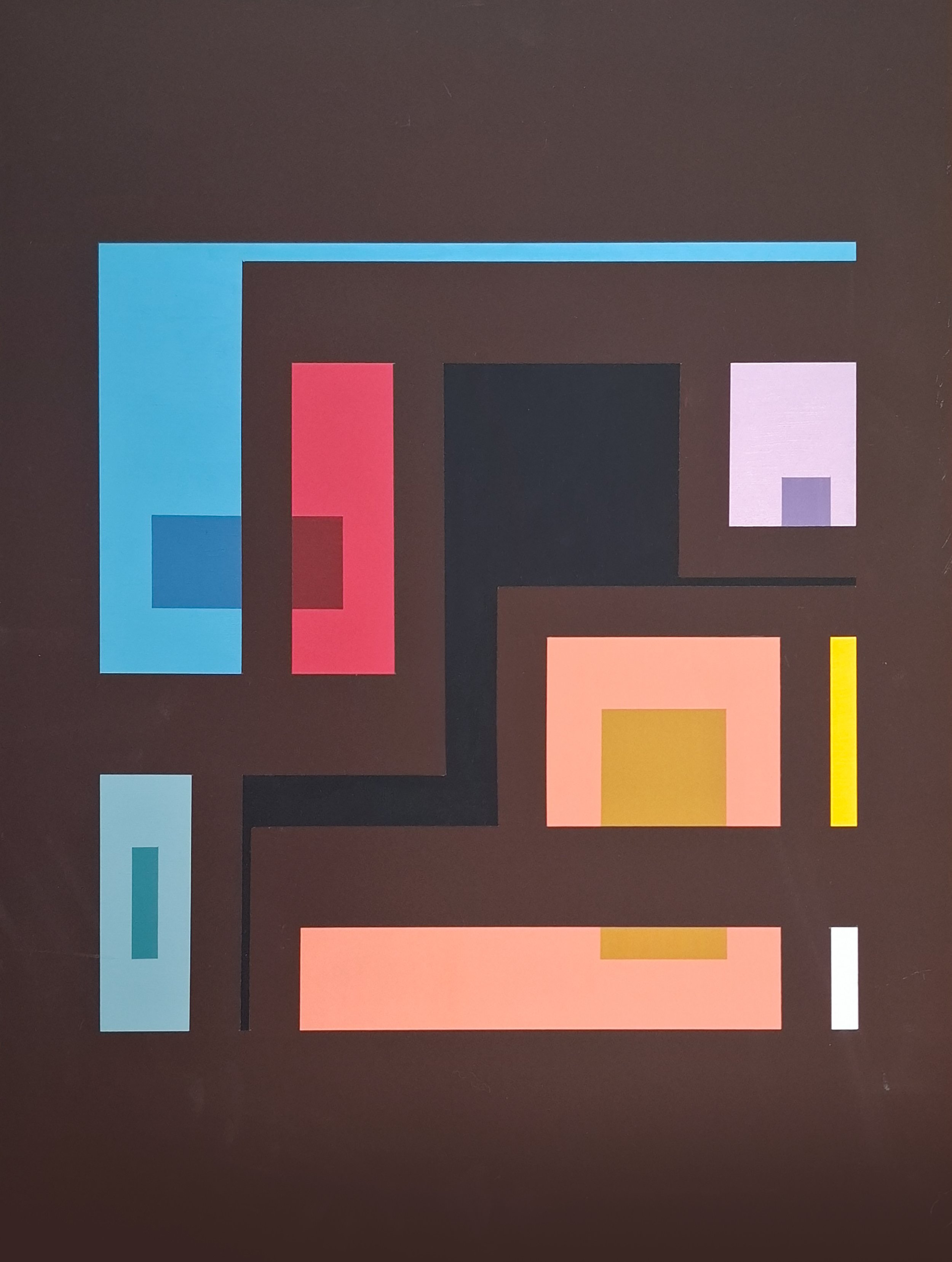

Image 2 of 4

Image 3 of 4

Image 3 of 4

Image 4 of 4

Image 4 of 4

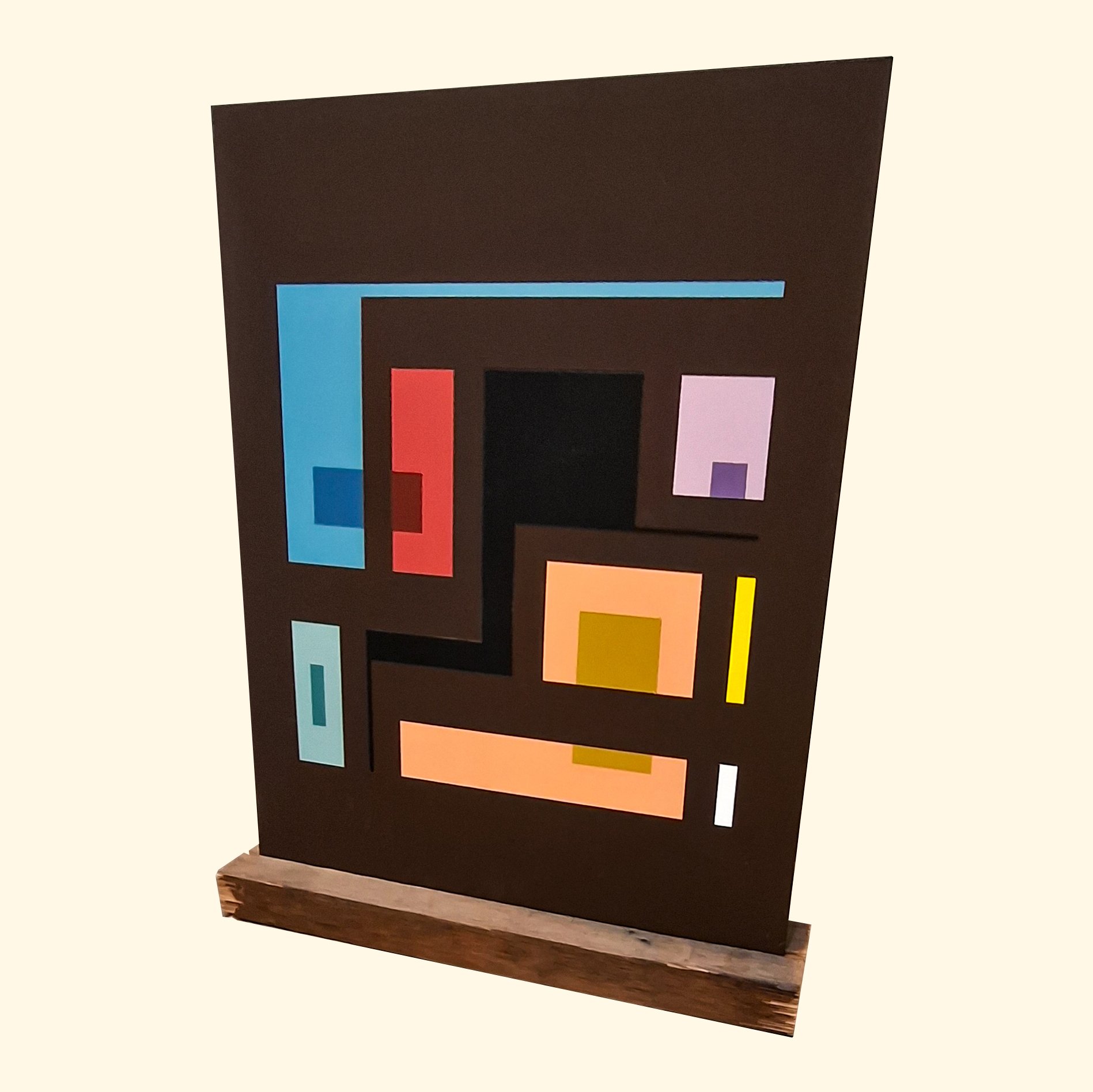

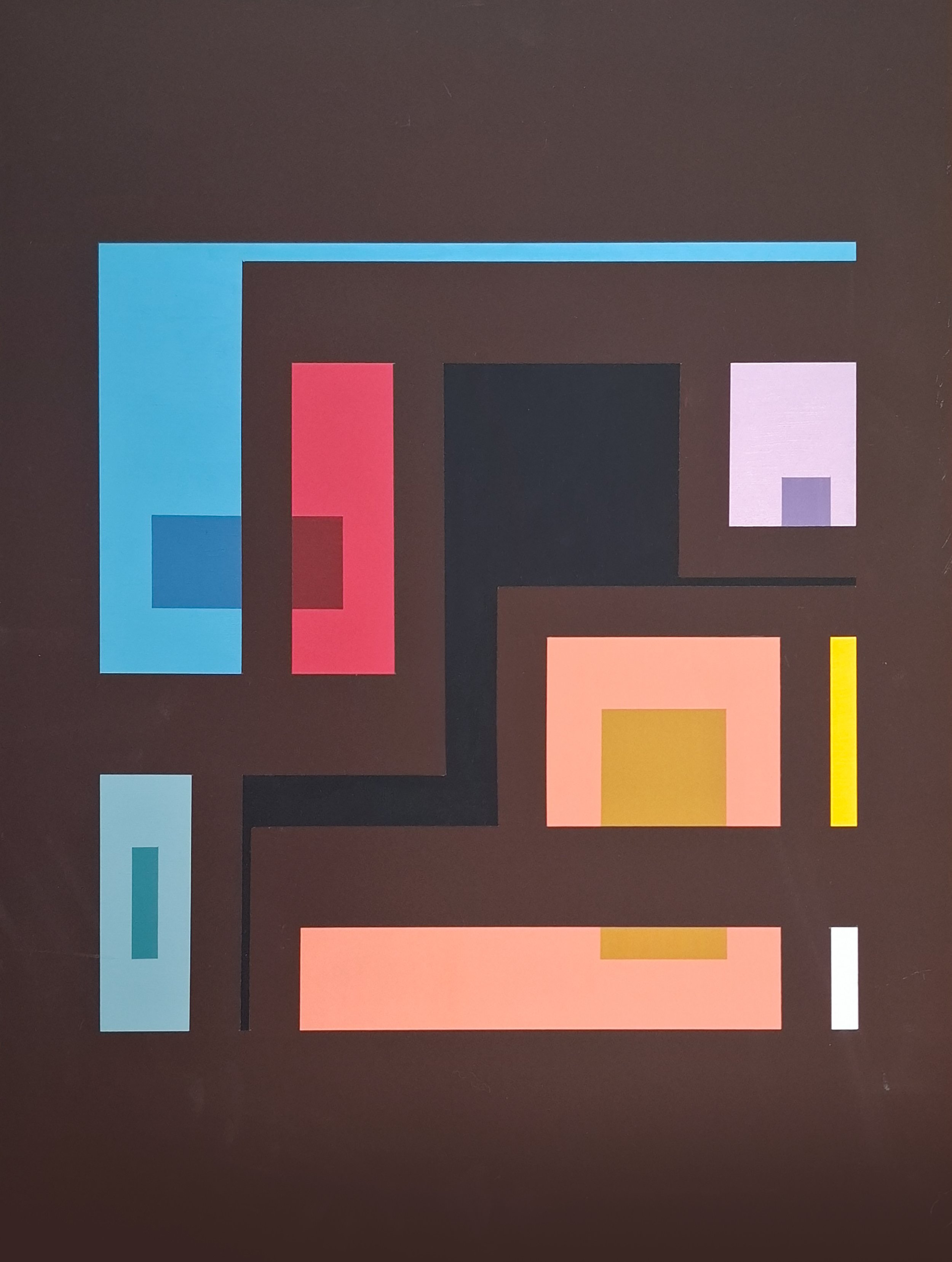

Facial (Mis)Recognition Test Stimulus 23.4: A Prosopagnosian or Pareidolian Portrait of Theseus Threading, 2023

Acrylic on board (ready to hang or can be mounted in reclaimed wooden base)

61 x 46 cm

This work is one in a series of geometric abstract paintings created as part of an ongoing project to philosophically investigate the significance of artwork titles, in this case conceptually set against the backdrop of our search for personal recognition and meaning in the age of facial recognition technology. The works raise questions about what it means to unwittingly be subjected to a test in much the same way that we are so often subjected to surveillance and technologies like facial recognition that are supposedly designed to protect us while simultaneously violating our privacy and posing risks such as the potential for wrongful identification and unjust treatment. To some, these paintings are nothing more than random compositions of interlocking lines and blocks of colour that might look almost digitally produced. Pondering this, one might begin to wonder what a facial recognition software program really ‘sees’ when it analyses an image of a human face captured by a camera. To a computer connected to an optical scanner, although each of us is a distinct pattern among millions in a database, we are effectively reduced to being nothing more a barcode or a QR code. What matters is that the pattern is then paired to the correct name and identity of the correct, real person.

As a framework for this series, these works are titled in such a way that they are presented as being part of a group experiment, hence the sequential ‘Test Stimulus’ numbers in the titles. All of the titles include references to pareidolia (the tendency to detect meaningful patterns where none exist, such as seeing faces in the contours of non-human objects) and the condition of prosopagnosia (aka face blindness), thereby providing an oblique but nonetheless implicit context for the viewer’s consideration as they view the works. In each title, these two concepts preface the words ‘Portrait of…’ followed by the unique identifier ‘[someone] [doing something]’, suggesting that there is not only a specific identity to perceive within the image but also suggesting that said identity is engaging in some activity (Theseus Threading, for example). It’s basic power of suggestion, but a consequence of this move is that the viewer is invited or more or less directed to consciously or subconsciously anthropomorphise what is otherwise clearly a non-representational artwork. (Without such titles, viewers would not be as inclined to attempt to see something that ostensibly isn’t there.)

Including the words ‘Facial (Mis)Recognition Test…’ further suggests that there are two categories or types of viewer: 1) those who can see some sort of ‘portrait’, and 2) those who do not or cannot see any such portrait. The word ‘Test’ implies that the viewer brings to the viewing experience some degree of interpretive capability or at least some degree of open-mindedness. Upending the commonly held belief that it is best for an artist to leave the interpretation of an artwork up to the viewer, the titles of these works declare that there is, indeed, a portrait to be seen if only one is capable of seeing it or open enough to see it. This creates a unique dynamic that differs from the conventional manners in which artworks are titled and therefore experienced. Furthermore, it raises questions about the validity of viewing an artwork without knowing its title, especially if it is the artist’s intent for the title to be communicated to the viewer. Unlike the ways in which one might perceive images in clouds or interpret inkblots in a Rorschach test, the ‘completeness’ of experiencing these particular paintings really does depend on the viewer knowing each work’s title in advance before viewing the work. While there is no such thing as passing or failing the challenge that each work presents, if the viewer can see what is proposed by the title, then naturally it is implied that the viewer tends toward the pareidolia end of the spectrum, and if not, then the implication—without judgment, of course—is that perhaps the viewer suffers from something akin to prosopagnosia (‘Can you not see what the title says you’re supposed to see?’).

As an artist, I am endlessly fascinated by the extent to which an artwork’s title can impact how the audience perceives the work. For better or worse, the addition of a few simple words on a label next to a painting, for instance, can completely transform how some viewers will interpret it. For this reason, some artists intentionally avoid titling their work at all so as not to influence the audience’s subjective interpretation of the work, arguing that the words themselves obscure a more direct emotional connection with the artwork. On the other hand, some artists intentionally give their works humorous, mysterious or completely arbitrary titles that have nothing to do with what’s on the canvas if for no other reason than to add a sense of intrigue to the piece. Some artists assign literal titles to their works. Some use numerical titles. Whereas some artwork titles are deliberate, thoughtful, interesting, clever, evocative and important to the vitality of the work and therefore likely to be honoured and upheld, others are total BS or just unnecessary, irrelevant or even detrimental to the work. History ultimately decides. Whatever the case may be, it is my belief that the title of an artwork, even if the artwork goes by Untitled, is never trivial; the identification of any artwork becomes as much a part of the artwork as the medium and content of the artwork itself and the setting within which the artwork is experienced.

Regarding the role of the audience in this ongoing investigation, one could argue that a viewer always does a disservice (both to the artist and to the viewer) by ignoring or disregarding the title of any artwork, but especially if the artist took great care in titling the work in a very specific way and intended for the title to be essential to the interpretation of the work. Doing so is tantamount to non-recognition, misrecognition and misidentification which in psychological and social terms are considered forms of oppression. While the viewing public should strive to respect an artist’s wishes when it comes to titles, it must also be said that there are, of course, many instances where an artwork's title, as commonly known, deviates considerably from the artist's original intention. Artwork titles can evolve over time. Many artworks acquire new, commonly accepted titles, even if they differ from the artist's original naming. This can happen due to discussions among the art community (collectors, gallerists, curators, critics and even the artists themselves). In any case, every instance of an audience viewing or experiencing a work of art involves some degree of recognition or misrecognition: you either ‘get it’ or you don’t… unless, of course, the artist never set out for there to be an ‘it’ for anyone to get. Some artists, as mentioned, intentionally distance themselves from their creations, opting instead to let the work ‘speak for itself’ by never assigning the any names or offering any descriptions.

Acrylic on board (ready to hang or can be mounted in reclaimed wooden base)

61 x 46 cm

This work is one in a series of geometric abstract paintings created as part of an ongoing project to philosophically investigate the significance of artwork titles, in this case conceptually set against the backdrop of our search for personal recognition and meaning in the age of facial recognition technology. The works raise questions about what it means to unwittingly be subjected to a test in much the same way that we are so often subjected to surveillance and technologies like facial recognition that are supposedly designed to protect us while simultaneously violating our privacy and posing risks such as the potential for wrongful identification and unjust treatment. To some, these paintings are nothing more than random compositions of interlocking lines and blocks of colour that might look almost digitally produced. Pondering this, one might begin to wonder what a facial recognition software program really ‘sees’ when it analyses an image of a human face captured by a camera. To a computer connected to an optical scanner, although each of us is a distinct pattern among millions in a database, we are effectively reduced to being nothing more a barcode or a QR code. What matters is that the pattern is then paired to the correct name and identity of the correct, real person.

As a framework for this series, these works are titled in such a way that they are presented as being part of a group experiment, hence the sequential ‘Test Stimulus’ numbers in the titles. All of the titles include references to pareidolia (the tendency to detect meaningful patterns where none exist, such as seeing faces in the contours of non-human objects) and the condition of prosopagnosia (aka face blindness), thereby providing an oblique but nonetheless implicit context for the viewer’s consideration as they view the works. In each title, these two concepts preface the words ‘Portrait of…’ followed by the unique identifier ‘[someone] [doing something]’, suggesting that there is not only a specific identity to perceive within the image but also suggesting that said identity is engaging in some activity (Theseus Threading, for example). It’s basic power of suggestion, but a consequence of this move is that the viewer is invited or more or less directed to consciously or subconsciously anthropomorphise what is otherwise clearly a non-representational artwork. (Without such titles, viewers would not be as inclined to attempt to see something that ostensibly isn’t there.)

Including the words ‘Facial (Mis)Recognition Test…’ further suggests that there are two categories or types of viewer: 1) those who can see some sort of ‘portrait’, and 2) those who do not or cannot see any such portrait. The word ‘Test’ implies that the viewer brings to the viewing experience some degree of interpretive capability or at least some degree of open-mindedness. Upending the commonly held belief that it is best for an artist to leave the interpretation of an artwork up to the viewer, the titles of these works declare that there is, indeed, a portrait to be seen if only one is capable of seeing it or open enough to see it. This creates a unique dynamic that differs from the conventional manners in which artworks are titled and therefore experienced. Furthermore, it raises questions about the validity of viewing an artwork without knowing its title, especially if it is the artist’s intent for the title to be communicated to the viewer. Unlike the ways in which one might perceive images in clouds or interpret inkblots in a Rorschach test, the ‘completeness’ of experiencing these particular paintings really does depend on the viewer knowing each work’s title in advance before viewing the work. While there is no such thing as passing or failing the challenge that each work presents, if the viewer can see what is proposed by the title, then naturally it is implied that the viewer tends toward the pareidolia end of the spectrum, and if not, then the implication—without judgment, of course—is that perhaps the viewer suffers from something akin to prosopagnosia (‘Can you not see what the title says you’re supposed to see?’).

As an artist, I am endlessly fascinated by the extent to which an artwork’s title can impact how the audience perceives the work. For better or worse, the addition of a few simple words on a label next to a painting, for instance, can completely transform how some viewers will interpret it. For this reason, some artists intentionally avoid titling their work at all so as not to influence the audience’s subjective interpretation of the work, arguing that the words themselves obscure a more direct emotional connection with the artwork. On the other hand, some artists intentionally give their works humorous, mysterious or completely arbitrary titles that have nothing to do with what’s on the canvas if for no other reason than to add a sense of intrigue to the piece. Some artists assign literal titles to their works. Some use numerical titles. Whereas some artwork titles are deliberate, thoughtful, interesting, clever, evocative and important to the vitality of the work and therefore likely to be honoured and upheld, others are total BS or just unnecessary, irrelevant or even detrimental to the work. History ultimately decides. Whatever the case may be, it is my belief that the title of an artwork, even if the artwork goes by Untitled, is never trivial; the identification of any artwork becomes as much a part of the artwork as the medium and content of the artwork itself and the setting within which the artwork is experienced.

Regarding the role of the audience in this ongoing investigation, one could argue that a viewer always does a disservice (both to the artist and to the viewer) by ignoring or disregarding the title of any artwork, but especially if the artist took great care in titling the work in a very specific way and intended for the title to be essential to the interpretation of the work. Doing so is tantamount to non-recognition, misrecognition and misidentification which in psychological and social terms are considered forms of oppression. While the viewing public should strive to respect an artist’s wishes when it comes to titles, it must also be said that there are, of course, many instances where an artwork's title, as commonly known, deviates considerably from the artist's original intention. Artwork titles can evolve over time. Many artworks acquire new, commonly accepted titles, even if they differ from the artist's original naming. This can happen due to discussions among the art community (collectors, gallerists, curators, critics and even the artists themselves). In any case, every instance of an audience viewing or experiencing a work of art involves some degree of recognition or misrecognition: you either ‘get it’ or you don’t… unless, of course, the artist never set out for there to be an ‘it’ for anyone to get. Some artists, as mentioned, intentionally distance themselves from their creations, opting instead to let the work ‘speak for itself’ by never assigning the any names or offering any descriptions.

Acrylic on board (ready to hang or can be mounted in reclaimed wooden base)

61 x 46 cm

This work is one in a series of geometric abstract paintings created as part of an ongoing project to philosophically investigate the significance of artwork titles, in this case conceptually set against the backdrop of our search for personal recognition and meaning in the age of facial recognition technology. The works raise questions about what it means to unwittingly be subjected to a test in much the same way that we are so often subjected to surveillance and technologies like facial recognition that are supposedly designed to protect us while simultaneously violating our privacy and posing risks such as the potential for wrongful identification and unjust treatment. To some, these paintings are nothing more than random compositions of interlocking lines and blocks of colour that might look almost digitally produced. Pondering this, one might begin to wonder what a facial recognition software program really ‘sees’ when it analyses an image of a human face captured by a camera. To a computer connected to an optical scanner, although each of us is a distinct pattern among millions in a database, we are effectively reduced to being nothing more a barcode or a QR code. What matters is that the pattern is then paired to the correct name and identity of the correct, real person.

As a framework for this series, these works are titled in such a way that they are presented as being part of a group experiment, hence the sequential ‘Test Stimulus’ numbers in the titles. All of the titles include references to pareidolia (the tendency to detect meaningful patterns where none exist, such as seeing faces in the contours of non-human objects) and the condition of prosopagnosia (aka face blindness), thereby providing an oblique but nonetheless implicit context for the viewer’s consideration as they view the works. In each title, these two concepts preface the words ‘Portrait of…’ followed by the unique identifier ‘[someone] [doing something]’, suggesting that there is not only a specific identity to perceive within the image but also suggesting that said identity is engaging in some activity (Theseus Threading, for example). It’s basic power of suggestion, but a consequence of this move is that the viewer is invited or more or less directed to consciously or subconsciously anthropomorphise what is otherwise clearly a non-representational artwork. (Without such titles, viewers would not be as inclined to attempt to see something that ostensibly isn’t there.)

Including the words ‘Facial (Mis)Recognition Test…’ further suggests that there are two categories or types of viewer: 1) those who can see some sort of ‘portrait’, and 2) those who do not or cannot see any such portrait. The word ‘Test’ implies that the viewer brings to the viewing experience some degree of interpretive capability or at least some degree of open-mindedness. Upending the commonly held belief that it is best for an artist to leave the interpretation of an artwork up to the viewer, the titles of these works declare that there is, indeed, a portrait to be seen if only one is capable of seeing it or open enough to see it. This creates a unique dynamic that differs from the conventional manners in which artworks are titled and therefore experienced. Furthermore, it raises questions about the validity of viewing an artwork without knowing its title, especially if it is the artist’s intent for the title to be communicated to the viewer. Unlike the ways in which one might perceive images in clouds or interpret inkblots in a Rorschach test, the ‘completeness’ of experiencing these particular paintings really does depend on the viewer knowing each work’s title in advance before viewing the work. While there is no such thing as passing or failing the challenge that each work presents, if the viewer can see what is proposed by the title, then naturally it is implied that the viewer tends toward the pareidolia end of the spectrum, and if not, then the implication—without judgment, of course—is that perhaps the viewer suffers from something akin to prosopagnosia (‘Can you not see what the title says you’re supposed to see?’).

As an artist, I am endlessly fascinated by the extent to which an artwork’s title can impact how the audience perceives the work. For better or worse, the addition of a few simple words on a label next to a painting, for instance, can completely transform how some viewers will interpret it. For this reason, some artists intentionally avoid titling their work at all so as not to influence the audience’s subjective interpretation of the work, arguing that the words themselves obscure a more direct emotional connection with the artwork. On the other hand, some artists intentionally give their works humorous, mysterious or completely arbitrary titles that have nothing to do with what’s on the canvas if for no other reason than to add a sense of intrigue to the piece. Some artists assign literal titles to their works. Some use numerical titles. Whereas some artwork titles are deliberate, thoughtful, interesting, clever, evocative and important to the vitality of the work and therefore likely to be honoured and upheld, others are total BS or just unnecessary, irrelevant or even detrimental to the work. History ultimately decides. Whatever the case may be, it is my belief that the title of an artwork, even if the artwork goes by Untitled, is never trivial; the identification of any artwork becomes as much a part of the artwork as the medium and content of the artwork itself and the setting within which the artwork is experienced.

Regarding the role of the audience in this ongoing investigation, one could argue that a viewer always does a disservice (both to the artist and to the viewer) by ignoring or disregarding the title of any artwork, but especially if the artist took great care in titling the work in a very specific way and intended for the title to be essential to the interpretation of the work. Doing so is tantamount to non-recognition, misrecognition and misidentification which in psychological and social terms are considered forms of oppression. While the viewing public should strive to respect an artist’s wishes when it comes to titles, it must also be said that there are, of course, many instances where an artwork's title, as commonly known, deviates considerably from the artist's original intention. Artwork titles can evolve over time. Many artworks acquire new, commonly accepted titles, even if they differ from the artist's original naming. This can happen due to discussions among the art community (collectors, gallerists, curators, critics and even the artists themselves). In any case, every instance of an audience viewing or experiencing a work of art involves some degree of recognition or misrecognition: you either ‘get it’ or you don’t… unless, of course, the artist never set out for there to be an ‘it’ for anyone to get. Some artists, as mentioned, intentionally distance themselves from their creations, opting instead to let the work ‘speak for itself’ by never assigning the any names or offering any descriptions.